What is your favorite book that you've written? This is a question I sometimes get. It's almost like asking a mother which one is her favorite child. Perhaps not. Maybe it more like asking a film director to identify his favorite film. The answer for me is difficult, but Seasons of Motherhood is high on the list.

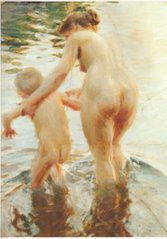

What is your favorite book that you've written? This is a question I sometimes get. It's almost like asking a mother which one is her favorite child. Perhaps not. Maybe it more like asking a film director to identify his favorite film. The answer for me is difficult, but Seasons of Motherhood is high on the list. One of the things I love about this book is the Monet prints on the cover and at the beginning of every chapter. This one of Camille Monet, Claude's wife. For a reminder of how wonderful Monet's paintings are, check out Claude Monet Gallery.

One of the things I love about this book is the Monet prints on the cover and at the beginning of every chapter. This one of Camille Monet, Claude's wife. For a reminder of how wonderful Monet's paintings are, check out Claude Monet Gallery.My research for this book was done primarily through reading biographies and autobiographies of well-known individuals who were significantly influenced by their mothers. I spent every Sunday afternoon one autumn and winter downtown at the Grand Rapids Public Library browsing through the biography section that is arranged alphabetically. In that four-hour time slot I would usually end up choosing about a dozen books that appeared to have good sections on the influence of the mother on the individual's life. I spent the week reading and incorporating material into my manuscript and would return the pile on the next Sunday.

This is a book of stories--including some of my own stories of the trials and joys of motherhood. The index includes such names as Abigail Adams, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Fanny Crosby, Dorothy Day, Annie Dillard, Walt Disney, Anne Frank, Sigmund Freud, and hundreds more.

If I were writing the book today it would be very different--500 pages instead of 250--and would include much more fiction, including children's fiction.

The Runaway Bunny

Here's a wonderful book for little ones:

Since its publication in 1942, The Runaway Bunny has never been out of print. Generations of sleepy children and grateful parents have loved the classics of Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd, including Goodnight Moon. The Runaway Bunny begins with a young bunny who decides to run away: "'If you run away,' said his mother, 'I will run after you. For you are my little bunny.'" And so begins a delightful, imaginary game of chase. No matter how many forms the little bunny takes--a fish in a stream, a crocus in a hidden garden, a rock on a mountain--his steadfast, adoring, protective mother finds a way of retrieving him. The soothing rhythm of the bunny banter--along with the surreal, dream-like pictures--never fail to infuse young readers with a complete sense of security and peace. For any small child who has toyed with the idea of running away or testing the strength of Mom's love, this old favorite will comfort and reassure.

Since its publication in 1942, The Runaway Bunny has never been out of print. Generations of sleepy children and grateful parents have loved the classics of Margaret Wise Brown and Clement Hurd, including Goodnight Moon. The Runaway Bunny begins with a young bunny who decides to run away: "'If you run away,' said his mother, 'I will run after you. For you are my little bunny.'" And so begins a delightful, imaginary game of chase. No matter how many forms the little bunny takes--a fish in a stream, a crocus in a hidden garden, a rock on a mountain--his steadfast, adoring, protective mother finds a way of retrieving him. The soothing rhythm of the bunny banter--along with the surreal, dream-like pictures--never fail to infuse young readers with a complete sense of security and peace. For any small child who has toyed with the idea of running away or testing the strength of Mom's love, this old favorite will comfort and reassure.Mothers & Other Monsters

This is a collection of short stories by Maureen F. McHugh that "wryly and delicately examines the impacts of social and technological shifts on families. Using beautiful, deceptively simple prose, she illuminates the relationship between parents and children and the expected and unexpected chasms that open between generations."

This is a collection of short stories by Maureen F. McHugh that "wryly and delicately examines the impacts of social and technological shifts on families. Using beautiful, deceptively simple prose, she illuminates the relationship between parents and children and the expected and unexpected chasms that open between generations."The Evil Stepmother is an autobiographical essay.

My nine-year-old stepson Adam and I were coming home from Kung Fu. "Maureen," Adam said--he calls me 'Maureen' because he was seven when Bob and I got married and that was what he had called me before. "Maureen," Adam said, "are we going to have a Christmas tree?"

"Yeah," I said, "of course." After thinking a moment. "Adam, why didn't you think we were going to have a Christmas tree?"

"Because of the new house," he said, rather matter-of-fact. "I thought you might not let us."

It is strange to find that you have become the kind of person who might ban Christmas Trees.

We joke about me being the evil stepmother. In fact, the joke is that I am the Nazi Evil Stepmother From Hell. It dispels tension to say it out loud. Actually, Adam and I do pretty good together. But the truth is that all stepmothers are evil. It is the nature of the relationship. It is, as far as I can tell, an unavoidable fact of step relationships.

We enter into all major relationships with no real clue of where we are going; marriage, birth, friendship. We carry maps we believe are true; our parent's relationship, what it says in the baby book, the landscape of our own childhood. These maps are approximate at best, dangerously misleading at worst. . . .

Sow Bear Love

I identify with Sue Hubbell, the mother of one child, a son, who struggled with her natural inclination to be overprotective. In her book, A Country Year, her words speak for me and my relationship with my only child, Carlton.

I identify with Sue Hubbell, the mother of one child, a son, who struggled with her natural inclination to be overprotective. In her book, A Country Year, her words speak for me and my relationship with my only child, Carlton.

When I was pregnant with Brian, I was pleased, curious and interested, but somehow detached and objective about the baby I was carrying. I was young, and had no notion of what he would mean to me.

After she held him for the first time, however, a powerful feeling of uncontrollable love suddenly manifested itself. That immediate intensity of emotion was part of my own experience.

There was fierceness to the love that was born the instant I saw him that startled and bewildered me. It was uncivilized, crude, unquestioning, unreasoning.

Sue did not begin to fully comprehend that love until some years later when she and her family were awakened one night while camping when "an old sow bear" wandered into their campsite and become separated from her cub. In the frantic moments before the cub wandered back, the fierce protective rage of this mother bear threatened the very lives of the startled campers. From this incident, Sue made analogies to her own life:

In order to become an adequate mother, I had to learn to keep the old sow bear under control. Sow-bear love is a dark, hairy sort of thing. It wants to hold, to protect; it is all emotion and conservatism. Raising up a man child in the middle of twentieth-century America to be independent, strong, capable and free to use his wit, intellect and abilities required other kinds of love. Keeping the sow bear from making a nuisance of herself may be the hardest thing there is to being a mother.

[Sue Hubbell, A Country Year: Living the Questions (New York: Random House, 1983), 89-91]

A SLAVE MOTHER'S ANGUISH

Josiah Henson offers this graphic story of the utter evil of slavery:

My brothers and sisters were bid off first, and one by one, while my mother, paralyzed by grief, held me by the hand. her turn came, and she was bought by Isaac Riley of Montgomery County. Then I was offered to the assembled purchasers. My mother, half distracted by the thought of parting forever from all her children, pushed through the crowd, while the bidding for me was going on, to the spot where Riley was standing. She fell at his feet and clung to his knees, entreating him in tones that a mother only could command, to buy her baby as well as herself, and spare to her one, at least of her little ones. Will it, can it be believed that this man, thus appealed to, was capable not merely of turning a deaf ear to her supplication, but of disengaging himself from her with such violent blows and kicks, as to reduce her to the necessity of creeping out of his reach, and mingling the groan of bodily suffering with the sob of a breaking heart? As she crawled away from the brutal man I heard her sob out, "Oh, Lord Jesus, how long, how long shall I suffer this way!" I must have been then between five and six years old. I seem to see and hear my poor weeping mother now. This was one of my earliest observations of men; an experience which I only shared with thousands of my race, the bitterness of which to any individual who suffers it cannot be diminished by the frequency of its recurrence, while it is dark enough to overshadow the whole after- life with something blacker than a funeral pall. [Josiah Henson, Uncle Tom's Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (London, 1877).

My brothers and sisters were bid off first, and one by one, while my mother, paralyzed by grief, held me by the hand. her turn came, and she was bought by Isaac Riley of Montgomery County. Then I was offered to the assembled purchasers. My mother, half distracted by the thought of parting forever from all her children, pushed through the crowd, while the bidding for me was going on, to the spot where Riley was standing. She fell at his feet and clung to his knees, entreating him in tones that a mother only could command, to buy her baby as well as herself, and spare to her one, at least of her little ones. Will it, can it be believed that this man, thus appealed to, was capable not merely of turning a deaf ear to her supplication, but of disengaging himself from her with such violent blows and kicks, as to reduce her to the necessity of creeping out of his reach, and mingling the groan of bodily suffering with the sob of a breaking heart? As she crawled away from the brutal man I heard her sob out, "Oh, Lord Jesus, how long, how long shall I suffer this way!" I must have been then between five and six years old. I seem to see and hear my poor weeping mother now. This was one of my earliest observations of men; an experience which I only shared with thousands of my race, the bitterness of which to any individual who suffers it cannot be diminished by the frequency of its recurrence, while it is dark enough to overshadow the whole after- life with something blacker than a funeral pall. [Josiah Henson, Uncle Tom's Story of His Life: An Autobiography of the Rev. Josiah Henson (London, 1877).A Mother's Day With Others in Mind

he first official Mothers' Day "celebrations" in America was actually work days for mothers, first organized by Anna Reeves Jarvis in 1858 to help improve sanitation in the Appalachian Mountains. During the Civil War, these work days were devoted to providing medical aid to soldiers serving both the Union and Confederate armies.

In 1872, Julia Ward Howe, a well-known philanthropist and poet, organized a Mother's Day for Peace to be commemorated on June 2. Her efforts began in Boston and spread to other cities along the eastern seaboard, where the day continued to be celebrated until the turn of the century. It was a day for mothers to band together and protest the senseless carnage of war:

In 1872, Julia Ward Howe, a well-known philanthropist and poet, organized a Mother's Day for Peace to be commemorated on June 2. Her efforts began in Boston and spread to other cities along the eastern seaboard, where the day continued to be celebrated until the turn of the century. It was a day for mothers to band together and protest the senseless carnage of war:Arise then, women of this day! . . . Say firmly: "Our husbands shall not come to us, reeking with carnage . . . . Our sons shall not be taken from us to unlearn all that we have been able to teach them of charity, mercy and patience. We women of one country will be too tender of those of another country to allow our sons to be trained to injure theirs.

These early celebrations of Mother's Day were not designed to focus on individual mothers themselves, but rather to allow mothers to speak out in word and deed on issues they deeply cared about.

In fact, the adoption of Mother's Day by the 63rd Congress on May 8, 1914 represented a reversal of everything the nineteenth-century mothers' days had stood for. The speeches proclaiming Mother's Day in 1914 linked it to celebration of home life and privacy; they repudiated women's social role beyond the household. . . . A day that had once been linked to controversial causes was reduced to an occasion for platitudes and sales pitches.

In fact, the adoption of Mother's Day by the 63rd Congress on May 8, 1914 represented a reversal of everything the nineteenth-century mothers' days had stood for. The speeches proclaiming Mother's Day in 1914 linked it to celebration of home life and privacy; they repudiated women's social role beyond the household. . . . A day that had once been linked to controversial causes was reduced to an occasion for platitudes and sales pitches. [Stephanie Coontz, The Way We Never Were: American Families and the Nostalgia Trap (New York: HarperCollins, 1992), 151-154]

Childless Mothers

There are countless images that come to mind when I think of childless mothers. Some are of women desperately longing to become pregnant and give birth; others mourning the loss of the child or children they once had. One of the most painful of these stories is forever etched in my memory through my reading and travel. Several years ago while vacationing out West with my family, we visited the Whitman Mission, a national historic site near Walla Walla, Washington. I had written about the ministry of Marcus and Narcissa Whitman in my history of missions text, and was now making a pilgrimage to the mission settlement they founded. There is much about their story that is gripping--most notably the Indian massacre that ended their lives. But the story that most touched my heart was that of a grief-stricken childless mother.

I write of that tragedy in From Jerusalem to Irian Jaya:

It was a late June Sunday afternoon at Waiilatpu. It was not just Sunday, but the Sabbath--a day of rest from the week's heavy labor. Marcus and Narcissa were engrossed in reading and little Alice was playing close by--or so they thought. When they suddenly realized she was missing, it was too late. The precious little two-year-old had wandered off and drowned in a nearby stream. . . . A year later a package arrived from back east with the little shoes and dresses Narcissa had requested from her mother. [101]

It was a late June Sunday afternoon at Waiilatpu. It was not just Sunday, but the Sabbath--a day of rest from the week's heavy labor. Marcus and Narcissa were engrossed in reading and little Alice was playing close by--or so they thought. When they suddenly realized she was missing, it was too late. The precious little two-year-old had wandered off and drowned in a nearby stream. . . . A year later a package arrived from back east with the little shoes and dresses Narcissa had requested from her mother. [101]I'll never forget walking along that stream and thinking back of the deep sorrow that arched over that isolated mission station in the summer of 1839. How did Narcissa survive such a painful tragedy? "A weaker woman could not have endured," I write, "but Narcissa's faith carried her through."

There are other kinds of childless mothers, and among them are those who grieve for children never born--whose heart aches for the little one they will never hold in their arms. Since biblical times, this has been one of the great sorrows of womanhood--described with such seeming finality by that haunting hollow word barren. Sarah was barren and so was Rachel and Hannah--all of whom later gave birth. But for many women, there is no such happy ending. Barren means barren.

ALICE WALKER REMEMBERS HER MOTHER

In her book, In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: The Creativity of Black Women in the South (1974), Alice Walker writes:

In her book, In Search of Our Mothers' Gardens: The Creativity of Black Women in the South (1974), Alice Walker writes:My mother adorned with flowers whatever shabby house we were forced to live in. And not just your typical straggly country stand of zinnias, either. She planted ambitious gardens - and still does - with over 50 different varieties of plants that bloom profusely from early March until late November. Before she left home for the fields, she watered her flowers, chopped up the grass, and laid out new beds. When she returned from the fields she might divide clumps of bulbs, dig a cold pit, uproot and replant roses, or prune branches from her taller bushes or trees - until it was too dark to see.

Whatever she planted grew as if by magic, and her fame as a grower of flowers spread over three counties. Because of her creativity with her flowers, even my memories of poverty are seen through a screen of blooms - sunflowers, petunias, roses, dahlias, forsythia, spirea, delphiniums, verbena . . . and on and on.

And I remember people coming to my mother's yard to be given cuttings from her flowers; I hear again the praise showered on her because whatever rocky soil she landed on, she turned into a garden. A garden so brilliant with colors, so original in its design, so magnificent with life and creativity, that to this day people drive by our house in Georgia - perfect strangers and imperfect strangers - and ask to stand or walk among my mother's art.

I notice that it is only when my mother is working in her flowers that she is radiant, almost to the point of being invisible except as Creator: hand and eye. She is involved in work her soul must have. Ordering the universe in the image of her personal conception of Beauty.

Her face, as she prepares the Art that is her gift, is a legacy of respect she leaves to me, for all that illuminates and cherishes life. She had handed down respect for the possibilities - and the will to grasp them.

For her, so hindered and intruded upon in so many ways, being an artist has still been a daily part of her life. This ability to hold on, even in very simple ways, is work Black women have done for a very long time.

A Mother's Sacrifice of Her Daughter

Catherine Booth, the co-founder of the Salvation Army, often confront the competing callings in her life--ministry and motherhood--and she dreaded passing that legacy on to the next generation. At the time of her daughter's wedding, she wrote of this struggle that plagued her:

Mothers will understand . . . a side of life to which my child is yet a stranger. Having experienced the weight of public work for twenty-six years, also the weight of a large family continually hanging on my heart, having striven very hard to fulfill the obligation on both sides, and having realized what a very hard struggle it has been, the mother's heart in me has shrunk in some measure from offering her up to the same kind of warfare. . . . The consecration which I made on the morning of her birth, and consummated on the day that I gave her first to public work, I have finished this morning in laying her again on this altar. [Catherine Bramwell-Booth, Catherine Booth (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1970), 341.]

From those words, it may seem as though Catherine Booth had given too much. Yet, measured in terms of those she helped--her far-extended family that included prostitutes and worse--she could never have given too much. And, as is so often true, her compassion multiplied itself. Many of those young women that were "reclaimed," went out to reclaim others and became full-time workers for the Salvation Army.